Exploring the Humor and Artistry of New Yorker Cartoons: A Conversation with Illustrator Sophie Lucido Johnson

The New Yorker magazine has long been revered for its unique blend of thought-provoking journalism, literary works, and exceptional cartoons. Renowned for its sophisticated humor and incisive wit, the publication's cartoons have become iconic, capturing the essence of contemporary life with a single frame.

Sophie Lucido Johnson, a talented cartoonist and author, has made her mark in the world of New Yorker cartoons. Johnson's illustrations effortlessly blend humor with poignant observations, shedding light on the complexities of relationships, personal experiences, and societal norms. Her distinctive artistic style and ability to infuse vulnerability into her work have garnered acclaim and a devoted following.

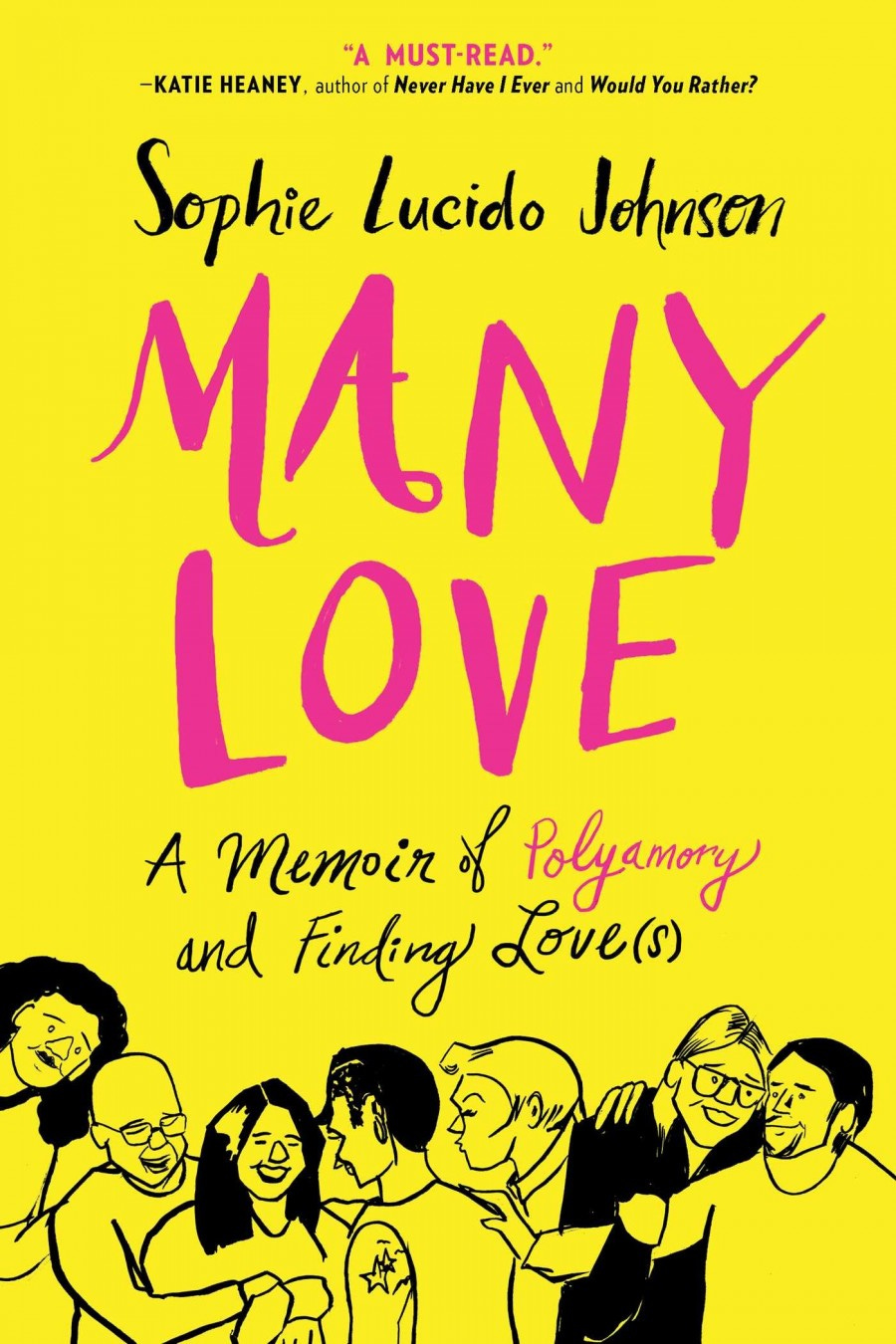

Johnson has authored two notable books that showcase her creative range and storytelling prowess. "Many Love: A Memoir of Polyamory and Finding Love(s)" is a candid exploration of her personal journey through polyamorous relationships, offering a unique perspective on love and intimacy. In "100 Crushes," Johnson presents a collection of illustrated stories that delve into themes of love, identity, and self-discovery, inviting readers to reflect on their own experiences.

In this interview, we dive into the world of New Yorker cartooning with an illustrator Sophie Lucido Johnson, delving into her artistic journey, creative process, and insights into the industry. We also explore her notable books, her captivating illustrations, and seek her advice for aspiring cartoonists.

Excerpts from the Interview :-

Q1) How did you get started as a cartoonist? Was it something you always wanted to do, or did you discover your talent later in life?

Sophie : In 2019, The New Yorker came in the mail, and it had been “taken over” by cartoons. I had been reading The New Yorker in the bath that year (sophisticated!), and I didn't initially realize that the issue I was about to read had been commandeered, but I distinctly remember the feeling I had when the reality of the coup dawned on me. I was TINGLY! I reacted MORE THAN A PERSON SHOULD TO A CARTOON-HEAVY ISSUE OF A HIGHBROW MAGAZINE! I was excited and jittery and gut-punched, and, once I had FINISHED reading the issue (and refilled the bath three times, because it was winter and the bath had gotten cold two times), I had made a decision: I wanted to be a cartoonist. Specifically, I wanted to be in a magazine like THIS, which was the coolest magazine I'd ever held.

It is unusual for me to have clarifying moments like this, so I decided to swallow my fear of submitting single-panel gags to The New Yorker (I'd sold a few Daily Shouts to them before, and felt that that was "good enough"), and start working a lot harder on achieving what felt like an impossible dream. I asked my friend Sammi Skolmoski (who is indescribably funny) if she wanted to brainstorm one-panels with me, and she said yes, and so we met up for a few hours and wrote HORRIBLE JOKES that we knew were bad. "How does anyone DO THIS?" I thought. Then it took me like six hours to badly draw out the ten bad jokes we'd come up with. The first one I did was of a tombstone that said, “She Never Had Cash.” I thought, "It can't be that hard to draw a tombstone." And actually, I was right. A tombstone is easy. If you need to feel good about your ability to draw, draw a tombstone.

Anyway, those ten were obviously rejected, but (cartoon editor) Emma Allen generously wrote back to say they were "promising" (!?!?!?!?!) and that we should keep trying. And that "no need to draw a line between the drawing and the caption." Eight months and over 100 cartoons later, WE SOLD ONE! I drank a gin on the roof of my house and thought about my enemies. I thought about how my enemies would find out that I had sold a cartoon, and how they would HATE IT and they would be MAD. And their imagined anger made me happy, and this is something about which I am not proud, but it's a fact of the story.

Q2) Your cartoons often have a humorous or satirical edge to them. What inspires you to take a light-hearted approach to serious or complex issues?

Sophie : You either laugh or you cry or you drink; I laugh a third of the time and cry two thirds of the time, and try not to drink at all.

Q3) What is your creative process like when coming up with a new cartoon idea? Do you start with a concept or a visual image, or does it vary depending on the project? The internet and social media have changed the landscape for cartoonists and other artists. How has your own creative process evolved in response to these changes, and what opportunities and challenges do they present for your work?

Sophie : I sit in a big, cozy chair and stare into space for a few hours with a notebook on my lap. I ask myself the question, “What have you noticed you’ve been noticing?” I got this question from a freelance seminar taught by Taffy Brodesser Akner, who is a genius at idea generation. I’m not sure that social media has changed my process regarding idea generation, although sometimes it gets in the way. Sometimes I’m thinking too much about what other people want to read.

Q4) Your illustrations often explore the complexities of relationships and human emotions. How do you go about capturing the nuances of these experiences in your work?

Sophie : If I’m doing that, it’s dumb luck.

Q5) The New Yorker is known for its rigorous editorial process. How do you navigate the editing and revision process when working on a cartoon for the magazine?

Sophie : Once you sell a cartoon to The New Yorker, it’s pretty much done and polished. The key is selling it in the first place; edits once it’s sold are comma-related, or, “can you make the caterpillar look a little less like a caterpillar?”

Q6) The New Yorker is famous for its iconic cartoons, many of which have become cultural touchstones. How do you approach the challenge of creating a cartoon that is both timely and timeless?

Sophie : Oh man, I guess I try not to think about that too much! Just put one foot in front of the other and try not to look down!

Q7) Many of your cartoons are deeply personal, drawing on your own experiences and relationships. Is it ever difficult to balance the vulnerability required to create this kind of work with the public nature of sharing it with a wide audience?

Sophie : Absolutely. I have definitely burned some bridges. I try to share my work with the people I write about before I publish it, and sometimes I’m surprised to learn that people are pretty upset with what I write about them. You experience your life in first person, and the person across from you is having a first person experience in a totally different perspective, and that can be difficult to fathom. Sometimes I wish I’d just throw in the towel and write novels instead.

Q8) You have also created comics and illustrations for other publications, including The Guardian and The New York Times. How do you adapt your style and approach for different audiences and contexts?

Sophie : Mostly, I’m copying artists I admire. I took a class from Chris Ware, and he brought in Lynda Barry to help us learn about learning from ourselves. That was the most influential art class I ever took; she helped me believe that what I needed to do was listen to my inner child and trust that Young Sophie had something to say to the world. I write the piece first, and then find the publication that I think will best fit the work.

Q9)Your memoir, "Many Love," is a deeply personal exploration of polyamory and non-traditional relationships. How did you approach the process of writing such a personal book, and what do you hope readers take away from it?

Sophie : I wrote a linear memoir about my love life and then my editor threw two thirds of it out the window and had me start from scratch! I wanted a book that would approach the topic of love from a lens that was less about romantic love and more about balancing romantic love with multiple friendships. I did a lot of research: I interviewed about 100 people and read a ton of books about polyamory, friendship, and the history of sex and sexuality. Ultimately, I came up with something I feel really proud of! It’s a weird book, because it has pictures and it doesn’t follow a chronological narrative, but it’s also not like any other book about polyamory. It is meant to be for readers who want to disrupt standard narratives about monogamous relationships, and not necessarily through the lens of sex parties or having multiple sexual partnerships.

Q10) “Dear Sophie" has become a beloved and highly relatable cartoon series for many readers. It has also been praised for its depiction of mental health and self-care. How do you navigate these sensitive topics in your work, and what kind of response have you received from readers? And how did you come up with the concept for this series, and what has been your favourite part of working on it?

Sophie : Wow, thank you! I started writing back to old diary entries as a personal project (and one I recommend to anyone who has old diary entries). I have heard mostly from people who have wanted to take on this project for themselves, and are looking for entryways. To this kind of person, my advice is: dive in! Pick any old diary entry and write back. Young You is back there, waiting.

Q11) You're also an educator and have taught cartooning workshops. What advice do you have for aspiring cartoonists, and how do you encourage your students to find their own unique voice? What are some of the challenges they can expect to face, and how can they stay true to their own unique vision and voice?

Sophie : My advice for making any kind of work is to get to the page, and I do have some advice about getting yourself to the page. It depends on your specific monster. There are four, by the way: four primary monsters whose entire reality hinges on a savage drive to keep you from writing anything ever at all. Here they are:

THE MIRROR MONSTER

Says to you:

“Nothing you make is good enough.”

“Your ideas are all stupid. Are those the best ideas you have?”

“Oh look! You’ve started something! Let’s look at it. (Pause.) Huh. That was a lot better in your head, didn’t it? Let’s scrap that and start again; you can do better.”

Battle this monster:

This is the same monster that knows exactly how much you weigh and reminds you that you are the only common thread in all your failed relationships. I’m pretty sure that even if you decided to live in an ashram in the Swiss Alps and meditate nine hours a day, this monster would be still be able to sniff you out and tell you all your faults.

So rather than go head-to-head with him every time, change your goals. If your dream is to get published in the New Yorker, think of your current work as necessary reps. Put another way: You’d never run a marathon without training, and everyone knows you shouldn’t beat yourself up over the practice runs.

One of the big secrets here is to stop re-reading. When I was writing my book, I told my adviser that I didn’t think I had it in me because until then I’d always written everything in one sitting. I couldn’t imagine putting something down and picking it up again and continuing to like it enough to want to finish it. She gave me the following piece of advice, which I have used ever since.

When you’re done drafting for the day, leave yourself a little note at the end of your work explaining what you’ve just done and what you’re about to do. You are not allowed to look at your early material at all until the project is done. Always stop when you are excited to keep going and you know just what will come next; NEVER stop when you are stuck.

The best work comes in surprising moments when you’re not expecting it. It pops up between paragraphs you thought you wanted to write and it startles you. The only way to write anything you’re going to like is to write anything. Focus on quantity over quality until you have a practice in place.

THE MONSTER WHO LIVES IN THE CLOCK

Says to you:

“Holy shit there are ten million things to do! You’re WAY too busy to make work today!”

“Ugh, do we REALLY have to get up at 5 a.m.? REALLY?”

“You don’t have enough time to sit for the two hours required to get any deep work going.”

Battle this monster:

Start small, but give yourself scheduled uninterrupted work time. There are rules:

You have to physically put the scheduled work time in your calendar. For the first week, do this every day for 30 minutes. Like, you have to put, “9:30 a.m. to 10:00 a.m.: UNINTERRUPTED WORK TIME.” And when Sadie texts you to see if you can do a 9:30 morning hang-out with her, you have to say, “No, I have something at that time; can you do 10:15?”

Set an alarm if you don’t trust yourself with a calendar.

Put your phone in airplane mode and turn the internet off on your computer. I know you think you need to research stuff while you’re writing, but you don’t. Make a note during your UNINTERRUPTED WORK TIME that you want to research Skittles or the origin of accordions or whatever, and you can research it later. There is somehow always time to browse the internet for information. It’s the actual work there is no time for.

Set a timer. For those 30 minutes, you have to be working. When you don’t know what to work on, you write, “I don’t know what to work on, I’m really feeling stuck.” Those paragraphs can always be moved or deleted. You just work (draw or write) through the 30 minutes and you don’t look back.

When the timer is up, you’re done! Make a habit of stopping there, at least at first, because you want to teach your mind that really, writing doesn’t take that much time at all, and even a little goes a long way.

THE SOCIAL MONSTERITE

Says to you:

“What’s the point of doing this if no one is holding you accountable for it?”

“None of your friends make stuff.”

“If you’re going to do something as tedious as writing or drawing, you should be getting paid for it.”

Battle this monster:

Join a group, and if you can’t find one to join, start one. Meetup.org has tons of these — just, scads and scads. But it is most helpful for me to do a Facebook search for exactly what I’m looking for: “women’s cartooning group Chicago”; “creative non-fiction writing group”; etc. Starting a group is also a surprisingly easy and interesting endeavor; in the past, I’ve posted on my social that I want to do a monthly drawing group and then I watch friends I had no idea were writers come out of the woodwork.

Also, consider starting a blog. You don’t need me to tell you that there are no shortage of platforms — Tumblr! Wordpress! Blogspot! Squarespace! LiveJournal is technically still a thing! — and there’s something about hitting the “Publish” button that makes all that solitary time with words feel more meaningful somehow. Plenty of people have figured out how to monetize their blogs, but if self-marketing isn’t your thing, just know that big publications that pay you like to see clips of your previous work; the more you have available for them to read, the likelier they are to hire you. If you want to be published, publish yourself.

THE MONSTER OF THE MIND

Says to you:

“What are you gonna draw? Huh? Your brain is empty.”

“OK, so you want to draw a memoir. Where are you going to start? Huh? Your brain is a dumb shell.”

“You have nothing worth drawing in that stupid, vestigial brain of yours.”

Battle this monster:

You, my friend, are an excellent candidate for MORNING PAGES. Julia Cameron, who invented them, says you need to wake up an hour earlier than you normally do, and I have to agree with her. You need to be up before everyone else is up. You need to be up and sitting at your notebook before you have checked your email and gotten sucked into the seductive lies of all that “needs to get done.” This will change your life: I promise.

It may also be worth going through a book of written prompts, or filling out a guided journal. Your ideas will spring forth once your pen is moving; it’s weird — as soon as you’ve really started something in earnest, all these NEW ideas start flooding your brain, and they’re all better than the CURRENT idea. (Like, today I feel like writing a blog post about king cake. But instead, I’m doing this one, because I started it and it deserves to be finished.) Follow the rule: Work on one thing at a time. As Henry Miller put it, “When you can’t create, you can work."

Thank you all for reading and a big thanks to Sophie Lucido Johnson for collaborating in today’s post!

It’s a pleasure!

If any of my readers here , wish to know more about the author or her writings. They can follow the links mentioned below :-

Website : http://www.sophielucidojohnson.com/

Instagram : https://www.instagram.com/sophielucidojohnson/

Twitter : https://twitter.com/sophielucidojo

Medium : https://sophielucidojohnson.medium.com/

Substack Newsletter :