The partition of India and Pakistan in 1947 stands as one of the most significant and tragic events in modern history. Millions of people were uprooted from their homes, communities were divided, and lives were forever changed. The partition's impact reverberated through generations, leaving deep scars and fractured memories. In an effort to understand the human dimensions of this historic event, writer Aanchal Malhotra embarked on a unique journey—one that unraveled the partition's history through the material remnants and personal stories of those who lived through it.

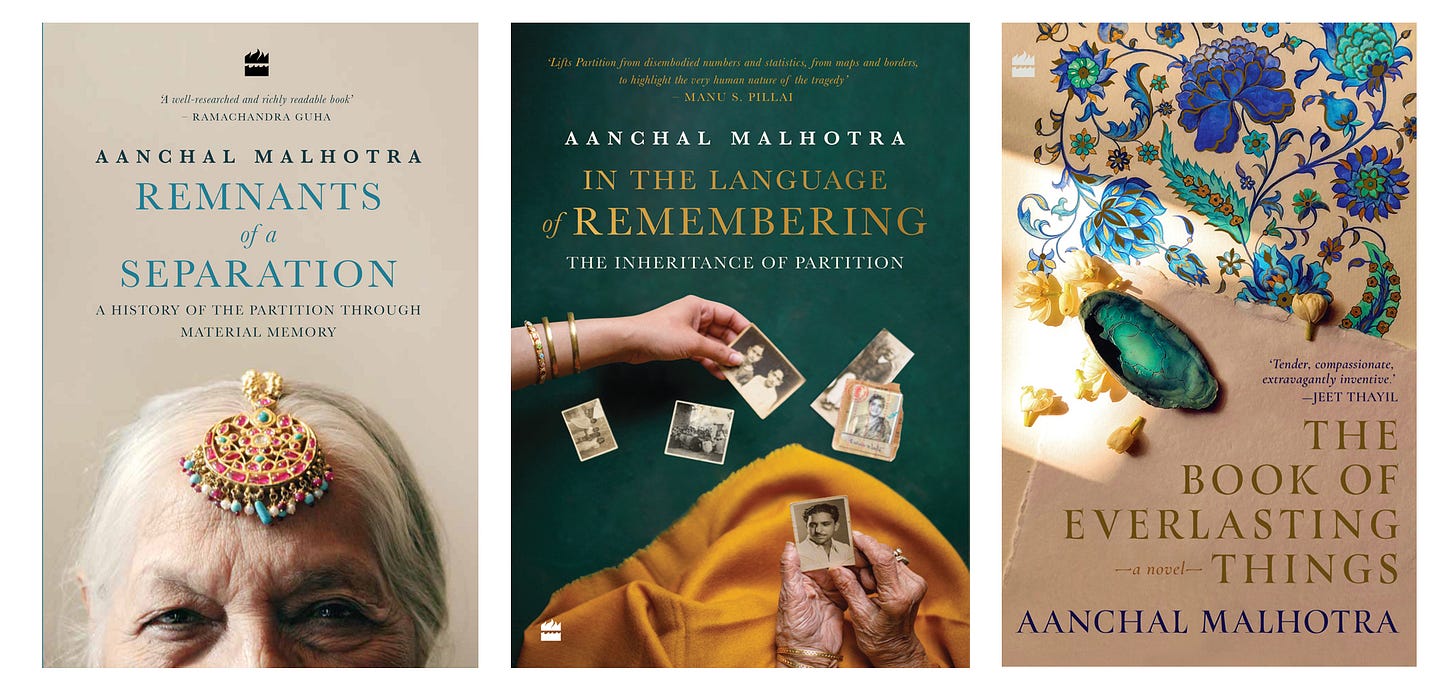

Malhotra's book, "Remnants of a Separation: A History of the Partition through Material Memory," offers a compelling exploration of the partition's aftermath and its profound effect on individuals and communities. In this captivating work, she uncovers the power of material artifacts as vessels of memory and witnesses to history. By collecting and documenting objects passed down through generations, such as photographs, letters, and everyday items, Malhotra brings to life the stories and emotions intertwined with these remnants.

Her meticulous research and poignant interviews with the owners and their families reveal the deep emotional connection people have with these objects. Through their narratives, she unveils tales of resilience, loss, and survival, painting a vivid picture of the partition's enduring impact on personal identities and collective memory.

In this interview, I had the privilege of speaking with Aanchal Malhotra to gain further insight into her work and the profound stories woven within "Remnants of a Separation." Join us as we explore the power of material memory and delve into the human dimensions of the partition, seeking to understand how personal narratives can illuminate the complexities of historical events and shape our understanding of the past.

Excerpts from the Interview : -

Q1) Can you tell us a bit about your journey as a writer? How did you first become interested in writing, and how did you develop your skills over time?

Aanchal : I came to writing from the fine arts. I was trained as a traditional printmaker and for the extent of my BFA and MFA degrees, was consumed by engraving, lithography, papermaking, letterpress, bookmaking, and aspects of colour, texture, surface, light, technique. It was a world of visual and sensory prompts. I was at a graduate program in Studio Art at Concordia University, Montréal, and after a year-long sabbatical, had returned to do my thesis (which needed to be a visual project) on the objects carried across during Partition, when inspired by the research I’d done during that time away, began thinking about writing. I always read a lot, but had never felt confident enough to write anything serious.

I’m being honest, though, even today three books later, because I don’t have any formal training in creative writing or literature, I tend to follow my own methodology of experimenting with research and form, which is inevitably derived from my work in the studio. Visual references combined with interviews and secondary research, like the words are being drawn from the images or the experience of being present in a particular place with a particular person. With each book, there is so much learning (and unlearning), that I feel I will always keep developing my skills.

Q2) Your book, Remnants of a Separation/Partition, is a fascinating exploration of the legacy of the Partition of India and Pakistan. Can you talk about how you first became interested in this topic, and what inspired you to write about it?

Aanchal : I was in my early twenties in 2013, on a sabbatical from graduate school, when I first discovered my family’s stories of Partition. These weren’t only stories of violence – as I’d expected them to be, having learnt of Partition only that in singular way through school textbooks and popular media – but also of resilience, strength, longing, confusion, friendship, hope, and the detail and depth of emotion with which they were narrated even decades later left me transformed. I felt almost embarrassed for not knowing them, for never asking, but I also realized how much this period of the past still influenced the present, both personally and politically.

More than anything though, I discovered that I was a listener, I had the desire to absorb and respond to these stories. As South Asians, we are a people of oral traditions and storytelling, which is such a visceral and intuitive trait, but it often means that things are not written down and can get lost or forgotten over time, over generations. I also noticed that we gave a lot more importance to the written archive – which could often be limited in access and inclusion – than to oral history – which began in our very homes, narrated in many tongues, relaying many perspectives (though the methodology does come with its own drawbacks). Maybe it was a sense of preservation then, that drew me to the recording of stories.

Q3) What was your writing process like for Remnants of a Separation/Partition? Did you conduct extensive research, interview people, or draw on your own personal experiences to write the book?

Aanchal : I first conducted fieldwork in India, Pakistan and the UK, which included oral history interviews, after which came the transcription and translation process, and finally, secondary research in the archives of India and the UK, to study some of the political documents and correspondence from that time, as well as secondary reading, which was based on each of the interviews I had chosen to include in the book. Only after that, did I begin to write, drawing mostly from the transcripts, but also using my own observations and experiences as points of reference. At the end, I felt sort of like an investigative journalist, putting together the stories of a time belatedly, piecing the past together through various perspectives and ways of feeling and returning.

Interviewing Uma Sondhi Ahmad, Kolkata, 2018

Interviewing Savitri Mirchandani, Delhi, 2016

Q4) How did you decide on the structure of the book, with each chapter focusing on a different object?

Aanchal : The form of the book was clear from the very beginning. The object had been an extraordinary catalyst to exhume memories of the past, and it was important to keep it as a central figure in each chapter. By way of touch, smell, sound, texture, the interviewee engaged with the object and recalled how it was used across the border and what their relationship had been to it, perhaps who it belonged to and why it was carried, and what it meant to them now. The stories strive to appreciate the object in its totality, not as something that blends into the landscape of the past but as a primary character around which the entire landscape is arranged.

Q5) How did you balance the personal stories of the families with the historical context of the partition?

Aanchal : I almost always followed the flow of our conversation because it felt most natural. But it was rare that people began speaking about Partition or even Independence from the beginning; the subject was usually woven into the conversation over time, and when they did bring it up, it was in the context of their own lives. Some would recall more specific details than others – dates, migration routes, a riot, a storm, a festival coinciding with their journey, the last exam they gave, a particular retaliation in a city or village, a political speech – which would be of great help to build the secondary research around that story. My attempts were never to overshadow the personal history for the person’s voice was always paramount, but to simply situate it within the larger landscape of what was happening at the time. The balance was often determined by the conversation itself – no two interactions were ever the same, they each bore their own unique details of remembering and forgetting, and it was important to respect that.

Q6) The objects in the book hold so much emotional weight and are almost like characters themselves. Can you talk about how you approached writing about these inanimate objects

Aanchal : Working in a studio makes you very conscious of material and form – you’re always touching, smelling, studying, comparing, observing things. Objects are powerful catalysts to record periods of time, but by themselves, they cannot speak. They require the infusion of memory and story, of history and historical context. Each crack, every streak of patina, an engraved initial, the small tear in fabric, the loose binding of a book, even the smell of an aged object has a story to it. I felt quite devoted to the objects, considering them equal protagonists to my interviewees, and wanted the writing to have a sort of visceral, tactile feeling to it. Each chapter is also accompanied by a photograph of the object, which was important to me.

Q7) Was there a particular object or story that surprised you during the writing process?

Aanchal : I think it was the stories of objects that people wished they had carried; I remember thinking of them as phantom objects, almost. A woman from Sindh lamented on leaving behind the rocking swing her baby loved. Or the many people who wished they’d carried soil from their native village – this longing really moved me.

Q8) Your book has been published both in India and internationally. Can you talk about the process of getting your work published, and any challenges you faced along the way?

Aanchal : Every writer, no matter how experienced or successful, will have challenges unique to each book they write. But I think the publishing industry itself is unequal – in terms of advances, agents, marketing budgets, reviews. There are discrepancies on every level, and this is a global issue.

For me, one of the biggest challenges was being taken seriously as a young, female writer of history, having no formal, academic training in the subject, which was largely dominated by older men. When I finished writing Remnants, I didn’t know whether 70 years after Partition, there’d still be an interest in the subject in South Asia, let alone anywhere else in the world.

It’s been nearly a decade since then, and some of my books still have no international editions, whereas others have been translated into various languages, and it feels amazing to see those editions and know that your work is traveling beyond your own land and space. But the one thing that’s remained consistent is my belief that a story well-told will find its place in the world, even though that may take time. I am not interested in trends, I don’t know what western expectations are for a writer of Indian origin at the moment. But what I do know is that I’m interested in the introspection of the human condition, which is long-lasting and universal. I am interested in recording the minutiae of everyday life, it’s what I am good at – listening, observing – and I want that work to be respected, wherever or whenever it is published in the world.

Q9) In addition to being a writer, you are also the co-founder of the Museum of Material Memory. Can you tell us more about the museum and its mission, and how it connects to your work as a writer?

Aanchal : The Museum of Material Memory is a crowd-sourced digital repository tracing family histories and social ethnography through heirlooms, collectibles and antiques from the Indian subcontinent, which I co-founded in 2017 with my friend, Navdha Malhotra. Through the intimate act of storytelling, each essay on the Museum website reveals not just a personal history of the object and its owner, but leads to the unfolding of a generational narrative spanning the traditions, cultures, customs, conventions, habits, languages, geographies, and history of the vast and diverse subcontinent. It was inspired by my work with objects of Partition, where the stories and the book acted as a kind of outline for others to research and write about the objects that were dear to them, but we very quickly expanded beyond the theme of Partition to welcome objects belonging to different geographies and time periods, originating anywhere in the subcontinent.

Q10) You have received numerous awards and accolades for your writing, including the Council for Museum Anthropology Book Award . What has been your proudest moment or achievement as a writer, and what motivates you to keep writing?

Aanchal : I’ve learnt to not gauge my value as a writer through literary awards. Don’t get me wrong, though - it feels incredible when one’s work is longlisted or shortlisted or wins anything, but it’s not what motivates me to continue doing what I do. I think some of my proudest moments have been to see the impact the work has made on a younger audience, prompting them to ask their family about the past, or to pick up older objects in their homes and learn the histories behind them. What gave me joy was to see stories that people had lived with in silence for decades gain resonance with readers even far removed from the tragedy – people all over world, who were learning about Partition for the first time through these oral histories.

Q11) Can you talk about any upcoming writing projects you have in the works, and what readers can expect from your future work?

Aanchal : It is difficult for me to begin writing something when I am still speaking about the previous book in interviews, etc. The shadow still lingers. These days I am only reading and observing.

Q12) Finally, can you recommend any books or authors that have inspired or influenced your own writing, either on the topic of Partition or more broadly?

Aanchal : Every few years, I return to the novel, Everything is Illuminated by Jonathan Safran Foer, I think its extraordinarily inventive. All The Light We Cannot See by Anthony Doerr left me utterly transported. Two of my favourite novelists are Anuradha Roy and Anuk Arudpragasm. In recent years, I have enjoyed The Indian Contingent by Ghee Bowman which documents the often-overlooked Indian soldiers present at Dunkirk during WW2, and The Deoliwallahs by Joy Ma and Dilip D’Souza, which details stories of Chinese Indians interned at the Deoli camp in Rajasthan after the 1962 war with China. In terms of Partition, I have learnt enormously from the works of Ritu Menon, Urvashi Butalia, Anam Zakaria, Kavita Puri, Yasmin Khan, Gyanendra Pandey, Andrew Whitehead, Nisid Hajari, Anis Kidwai, Fikr Taunsvi.

Thank you all for reading and a big thanks to Aanchal Malhotra for collaborating in today’s post!

It’s a pleasure!

If any of my readers here , wish to know more about the author or her writings. They can follow the links mentioned below :-

Wikipedia : https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Aanchal_Malhotra

Website : https://www.aanchalmalhotra.com/

Work : https://www.aanchalmalhotra.com/work/remnants-of-a-separation/

Instagram : https://www.instagram.com/aanch_m/

Twitter : https://twitter.com/aanchalmalhotra

Goodreads : https://www.goodreads.com/author/show/17093338.Aanchal_Malhotra

wow! thank you for interviewing her! such good questions!