Before the algorithm found us, there was harry potter.

I sometimes wonder whether Harry Potter could exist the same way today.

Not the franchise - of course it could. The theme parks, the merchandise, the discourse, the adaptations stacked neatly into content calendars. But the experience? The private, almost sacred act of reading Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone - before the internet told us how to feel about it?

That feels harder to recreate.

When I first read Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone, there was no social media to archive the moment. No fandom wars. No algorithms amplifying hot takes before the last page was turned. Reading was slow, solitary, and deeply personal. You didn’t consume stories; you lived inside them.

And maybe that’s why, rereading the first book now - in my thirties - it doesn’t feel dated. It feels preserved.

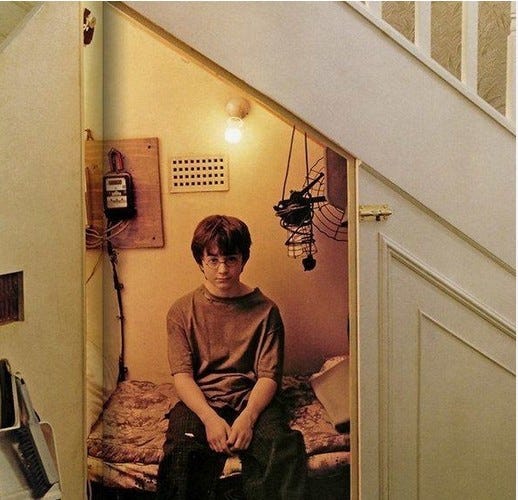

The opening chapters remain quietly brutal. Before magic, Rowling gives us neglect. Harry Potter is not introduced as “the boy who lived,” but as a child who survives emotional erasure. The cupboard under the stairs is not metaphorical; it is literal. His relatives do not hate him dramatically; they inconvenience him into invisibility. It’s mundane cruelty, the kind that doesn’t leave marks but shapes a person forever.

This grounding is important. J. K. Rowling understood something that many fantasy writers miss: wonder only works if the ordinary world is unbearably small. Hogwarts dazzles because Privet Drive suffocates.

So, when Hagrid arrives and says, “You’re a wizard, Harry,” the line doesn’t feel triumphant. It feels corrective. Someone is finally telling Harry that his life makes sense. That what he endured was not meaningless. That his difference is not a flaw.

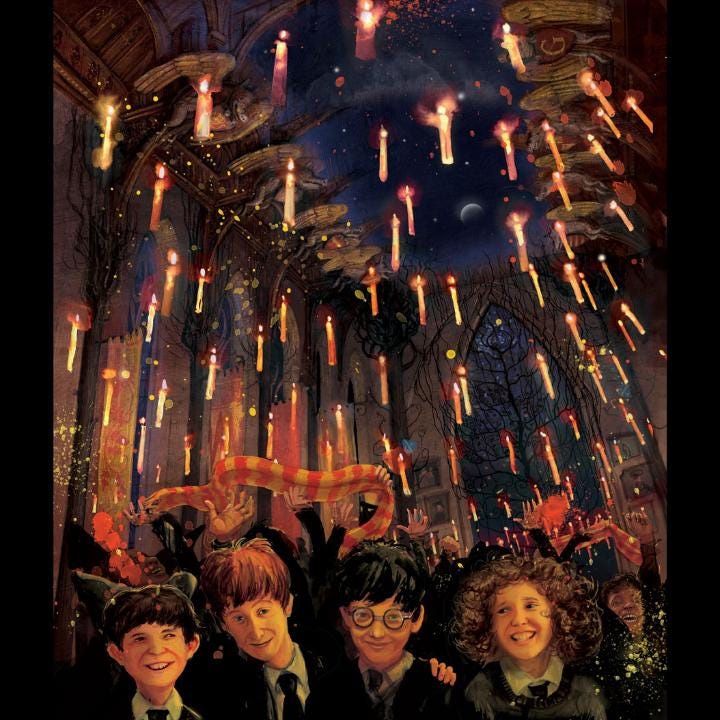

The magic of the first book is not spectacle-driven. Diagon Alley doesn’t explode into view; it reveals itself slowly. Platform Nine and Three-Quarters requires blind faith - running straight at a wall with a trolley, hoping reality bends. Hogwarts itself isn’t utopia; it’s structure. Classes. Homework. Authority. Consequences. In hindsight, that may be why it resonated so deeply. Hogwarts isn’t freedom - it’s care.

As children, we read Hogwarts as escape. As adults, we recognize it as something rarer: a functioning system where curiosity is rewarded and adults - however flawed - are present. Even Snape’s cruelty, McGonagall’s strictness, Dumbledore’s distance exist within a framework that protects children. That, now, feels almost fantastical.

What hits hardest on rereading are the quiet moments - the ones that didn’t make it into merch lines or memes.

The Sorting Hat scene is less about houses and more about fear: the fear of being placed somewhere you don’t belong. The friendship between Harry, Ron, and Hermione isn’t forged through heroics, but through shared awkwardness and rule-breaking - bathroom trolls, lost house points, detentions. It’s clumsy, organic friendship, the kind that forms before you know who you’ll become.

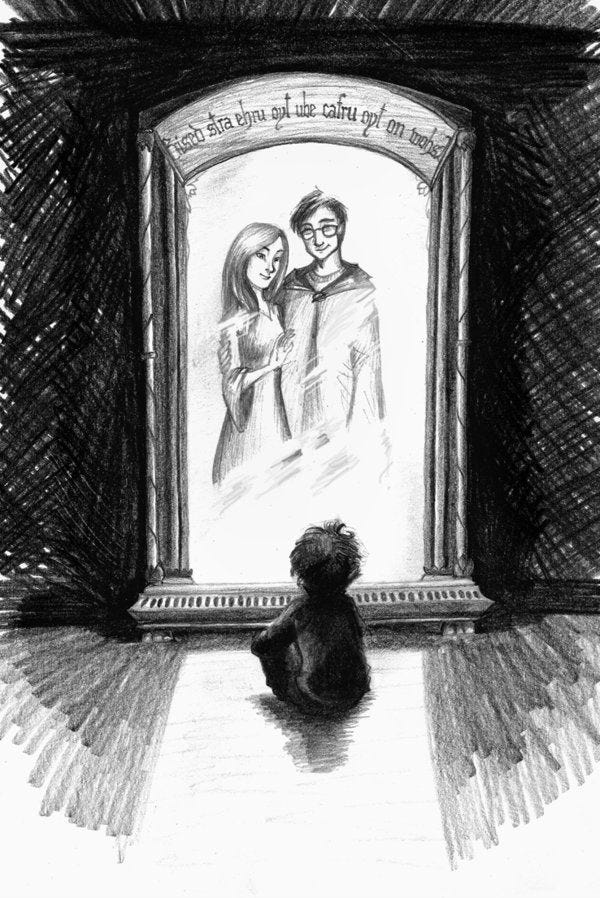

And then there is the Mirror of Erised.

“It shows us nothing more or less than the deepest, most desperate desire of our hearts.”

As children, the mirror was sad. As adults, it is devastating. Harry doesn’t see power. He doesn’t see glory. He sees his parents. The first book understands grief long before the series becomes about death. And Dumbledore’s warning - “It does not do to dwell on dreams and forget to live”- lands differently now, in an era where longing is constantly monetized.

Even Voldemort, barely present, feels appropriate. In the first book, evil is unfinished, spectral, undefined. The real antagonist is loneliness. The real victory is belonging.

The film adaptation- Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone - gave us something precious: a shared visual language. The floating candles. The Great Hall. John Williams’ score wrapping childhood in sound. The movie didn’t betray the book; it translated it. But translation always costs something. Cinema rushes where books linger. It shows magic, but it cannot sit inside thought the way prose can.

Which brings us to the upcoming Harry Potter TV series - a project greeted not with pure excitement, but with cautious longing.

What readers want now isn’t spectacle. We’ve had that. What they want is texture. Slowness. The parts the movies skimmed over: ordinary classes, long meals, awkward silences, the emotional weather of childhood. A series format has the potential to restore what the first book valued most: time.

Expectations, of course, are impossibly high. Everyone carries their own Hogwarts. Everyone remembers the book differently because we met it at different ages, in different silences. Nostalgia is not just memory - it’s identity.

But perhaps the success of a new adaptation shouldn’t be judged by how closely it recreates our childhoods. Perhaps it should be judged by whether it remembers the first book’s central truth:

That magic doesn’t shout.

That belonging is revolutionary.

That being seen can change a life.

Reading Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone now, in an age of endless commentary, feels like returning to a version of ourselves who read without posting, believed without irony, and waited without refreshing a screen.

Before the algorithm found us, there was a boy in a cupboard who learned - slowly, gently - that the world could be bigger.

That promise still holds.

beautifully written. the whole article resonated to the core