An Interview with Alex Edmans on Facts, Narratives, and Intellectual Honesty

Alex Edmans is not the kind of academic who confines his arguments to footnotes and faculty seminars. A professor of finance at London Business School and a former investment banker at Morgan Stanley, he has spent much of his career operating at the uneasy intersection of markets, data, and public belief - where numbers are often less powerful than the stories built around them.

Over the past two decades, Alex has emerged as one of the most visible advocates of evidence-based thinking in finance and corporate governance. His research on executive compensation, long-termism, and sustainability has been cited not only in academic journals but also in policy debates, parliamentary hearings, and boardrooms. His first book, Grow the Pie, made a rigorous yet accessible case for stakeholder capitalism at a time when ESG was still viewed with skepticism in mainstream finance.

But May Contain Lies, his latest book, marks a noticeable shift in emphasis. Rather than advancing a clear framework or prescribing a solution, Edmans turns his attention to a more uncomfortable question: how selective truths - statistics that are technically correct but strategically framed - shape public discourse, investment decisions, and policy outcomes. The book arrives at a moment when data is abundant, trust is scarce, and disagreement is often treated as moral failure rather than intellectual difference.

What makes Alex an especially compelling guide through this terrain is that he does not position himself outside the problem. He writes as someone who has benefited from popular narratives - particularly around ESG - while also becoming increasingly uneasy with how weak evidence is often amplified when it aligns with fashionable conclusions. In an era where academic research, corporate reporting, and journalism are all subject to their own incentive structures, May Contain Lies argues that misinformation is less about outright falsehoods and more about what gets emphasized, ignored, or oversold.

I spoke with Alex about the experiences that led him to write the book, the dangers of treating complex issues as morally binary, and how readers, especially investors, analysts, and journalists - can cultivate skepticism without sliding into cynicism. The conversation ranged from CEO pay and ESG research to LinkedIn pile-ons, academic publishing incentives, and the subtle psychological habits that shape how we decide what to believe.

Excerpts from the Interview:

Q1) May Contain Lies is about how we’re misled by selective truths rather than outright falsehoods. What was the moment (or accumulation of moments) that made you feel this book had to be written now?

Alex: Even though my day job is an academic, I enjoy interacting with practitioners, policymakers, and the general public: in particular, to apply the insights of academic research to real-world problems. In doing so, I learned that how people respond to research depends much more on whether they like its findings rather than on whether the research is rigorous. If it confirms what they want to be true, they lap it up uncritically; if it’s an inconvenient truth, they dismiss it.

There was no one particular moment that triggered the book, but an accumulation of moments as you say. One episode was in 2016-7 when there was controversy on CEO pay and a House of Commons inquiry in the UK. People were widely proclaiming evidence that CEOs are overpaid, and the higher CEO pay is, the worse the company performance. Indeed, when I testified in the House of Commons, the witness before me made exactly that statement, when the very evidence they cited actually showed the opposite. Episodes like those prompted my TED talk “What to Trust in a Post-Truth World” about the importance of being discerning with evidence.

Unfortunately, misinformation has only since got worse. Now people parade evidence that demographic diversity always improves company performance, and that ESG always boosts financial returns. I’d love this to be true, being an ethnic minority and an ESG advocate (indeed, my first book Grow the Pie was on the business case for sustainability).

But the evidence is far weaker than typically claimed. DEI and ESG research are now increasingly produced by consultancies (rather than academics with research expertise) and undertaken as a marketing exercise to improve their image, rather than to search for the truth, but many people ignore these skewed incentives to accept a convenient message.

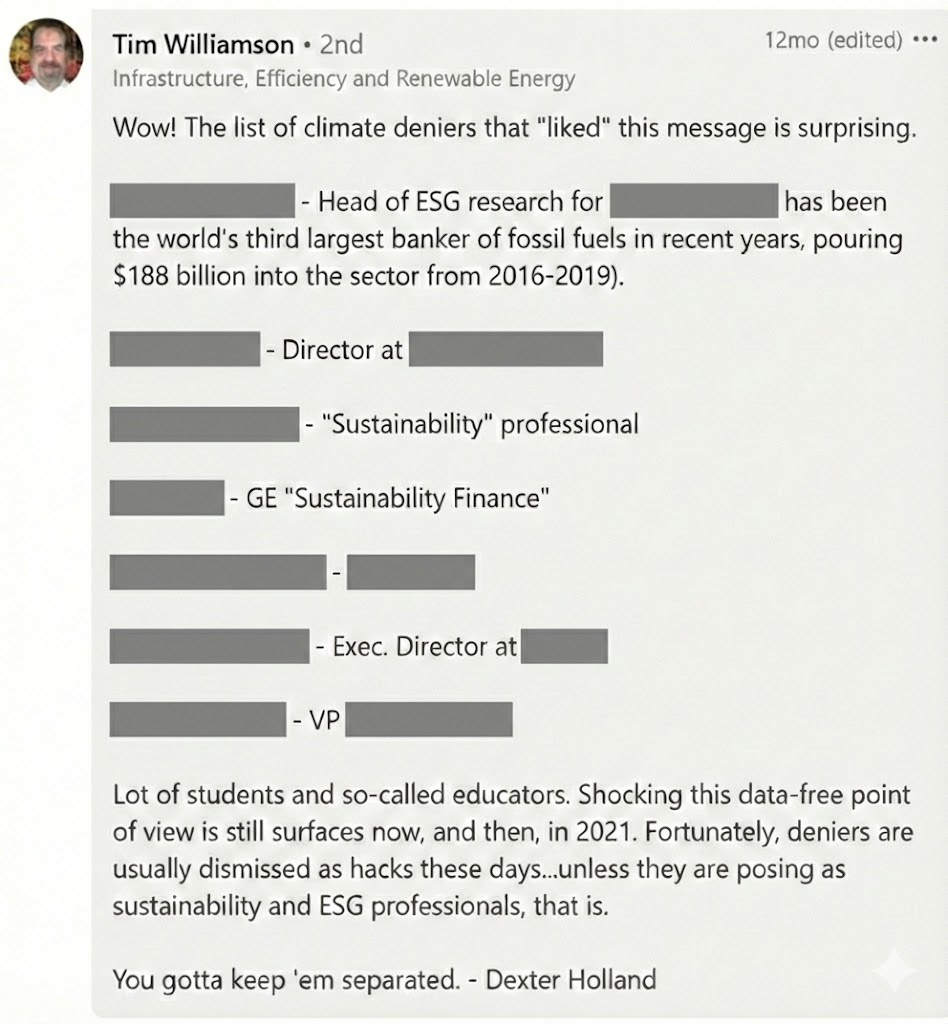

Worse still, people who challenge the evidence are sometimes portrayed as racist, sexist, and anti-science. Indeed, on LinkedIn, even “liking” a message that expresses a different view can be met with you being named and shamed and being labelled a climate denier.

I wanted to highlight the shades of grey in issues that are often portrayed in black-and-white and thus allow for people to express different viewpoints without being cancelled.

Q2) You’ve spent much of your career encouraging evidence-based thinking in finance. Did you initially see this book as an extension of your academic work or did it evolve into something broader, almost philosophical?

Alex: It was indeed an extension of my academic work beyond finance to other areas. Unfortunately, misinformation is not just an issue in finance, but other fields such as science, politics, and health advice. Thus, its damage is not limited to lower company profits, but extends to which politicians get elected, how we prevent and cure disease, and how we combat global problems such as climate change.

Q3) You argue that many misleading claims are technically “true” but still deceptive. How should readers train themselves to spot truthful statements that mislead, especially when time and attention are limited?

Alex: If we see a statement we’d like to be true, imagine the opposite result - one that makes us feel uncomfortable - and ask how we might challenge it. Take a study which finds that more sustainable companies deliver better company performance. That’s a correlation, but we’re tempted to interpret it as causation: sustainability improves performance. Before we do so, imagine the study found that sustainable companies perform worse. We don’t like that result, so we’ll try to claim it’s not causation. Perhaps CEO quality affects both - maybe a bad CEO worsens performance, and a bad CEO invests in sustainability because s/he’s distracted from the core mission.

Now that we’ve alerted ourselves to the possibility of alternative explanations, ask ourselves whether the same alternative explanations may be a problem for the original result - the one we want to be true. Maybe good CEOs improve performance, and good CEOs invest in sustainability because they’re forward-thinking. Then, it might not be causation.

The power of “imagine the opposite” is it highlights that the tools for discernment are already within us. You don’t need to do a PhD in statistics or check every footnote, both of which are impractical. Indeed, whenever I see a study posted on LinkedIn that people don't like the sound of, there's no shortage of challenges such as “correlation is not causation”, “that could be a single hand-picked anecdote”. The idea of "imagine the opposite" encourages us to be as equally skeptical of something we do like as something we don't.

Q4) One of the book’s strongest themes is how incentives shape narratives: whether in academia, media, or corporate reporting. In your view, which ecosystem today produces the most dangerous distortions: research, journalism, or business?

Alex: Unfortunately, all of them are dangerous. Being an academic, I’d like to claim that academia was pure and the real world is awash with misinformation, and if only practitioners listened more to academics like me, the world would be a better place. But that’s not the case. All three ecosystems are inhabited by humans, and all humans have their biases - researchers, journalists, or businesspeople. When I did my pro-ESG research nearly 20 years ago, academic journals wanted to reject it because ESG wasn’t hot back then and most people thought that something as fluffy as ESG couldn’t possibly pay off. Nowadays, journals are falling over themselves to accept ESG papers, because it’s popular. And all humans respond to incentives. At least until a couple of years ago, academics could have - and have had - significant impact if they release pro-ESG or pro-DEI research.

Q5) You’re careful not to position yourself as anti-data or anti-storytelling. What does responsible storytelling with data look like to you?

Alex: Like my views on many things, the answer is not black-and-white or either/or, but both/and. Often academics may dismiss a story as an anecdote, and put their faith in regressions that use large-scale data. But a regression coefficient is nowhere near as memorable as a story - from the days of the oral tradition, stories have always been powerful. Thus, we should have a one-two punch, of a story that’s then backed up by large-scale research, so that it’s not a single anecdote.

Q6) The book repeatedly warns against over-relying on single studies or eye-catching statistics. Yet policy, markets, and media often demand quick conclusions. How do we balance intellectual humility with the need to act?

Alex: We should indeed recognize that perfect should not be the enemy of good: 90% of the answer now may be preferable to 100% of the answer in three years’ time. But if we want to take action on an issue why where the scientific consensus is still emerging, do so in a more moderate way. For example, a DEI policy might be mindful of unconscious bias and expand the net beyond the traditional applicant pool. But it should not necessarily involve quotas for particular minority groups or linking CEO pay to simple DEI metrics in the absence of clear evidence that demographic diversity improves performance.

Q7) This book blends academic rigor with narrative clarity. How did you decide what to simplify and what complexity to preserve without diluting the argument?

Alex: This is actually a challenge that exists even within academia, and even if an academic has no interest in interacting with the real world. To be a successful academic, your research should have impact beyond your narrow sub-field, and thus it needs to be accessible to those who work in other areas. Thus, your research should absolutely contain the technical detail in the body of the paper, or maybe in the appendix, but the introduction should summarise the research at a high level. And it’s the same for writing for a non-academic audience.

Some academics look down on other academics whose work has impact on practice - they claim that their work must be “dumbed down” if it can be read by the unwashed masses. I believe that such an attitude is highly problematic. First, research is often funded by practitioners (e.g. through alumni donations) or the public (e.g. through research grants) and thus must be relevant for the real world. Second, the same skill of making your research relevant and widely applicable improves not only practitioner impact, but also academic impact.

Q8) Did your writing process differ from Grow the Pie? Was May Contain Lies harder to write - given that it challenges readers rather than offering a clear framework or prescription?

Alex: It did not. The challenge of making something accessible for a general audience exists for an academic research paper, for a Wall Street Journal op-ed, and for a book. May Contain Lies might seem to be a more challenging book than Grow the Pie as it aimed to appeal to readers outside business and finance, my traditional home. But, because it was my second book, I was already used to writing a book for practitioners (rather than academics) and so I was able to move to the next stage of the learning curve, which was a book for both business and non-business practitioners alike.

Q9) How much rewriting does it take for you to feel a paragraph is both accurate and accessible? Are you ruthless with edits, or do you let ideas breathe?

Alex: A huge amount, because I’m rather obsessive and compulsive about writing! In my academic papers, I’m often the lead writer: I often have coauthors who are stronger than me in theoretical modelling or running regressions, but I take responsibility for ensuring that the writing is as precise as possible. What you write ends up published in a scientific journal and forms (a very small) part of the “canon”, so it needs to be as good as it can be. I feel the same about my books, even though they are a couple of books out of the millions that exist: while I can’t affect the other million, I can try to make mine as good as they can be. I will write, re-write, re-re-write, and then ask research assistants to challenge my writing.

The success of a book seems to depend more on marketing and publicity than its inherent quality, so if my only goal was sales, that’s time I should reallocate to those other activities. However, I’m unable to shake off my academic tendencies which is to view both a research paper and a book as science, and want it to be as precise as possible.

Q10) ESG analysis features prominently in debates around data misuse and selective evidence. How should investors distinguish between meaningful long-term signals and ESG storytelling?

Alex: It is to place greater weight on academic research. Often people view “academic” as the opposite of “practitioner”, and practitioners may think they should lean on real-world examples rather than academic studies. But academics and practitioners go after the same questions (e.g. “does sustainability cause better company performance”); the difference is that the former have the time and space to really nail a result. Thus, rather than falling for a single story or case study, to learn research that analyses hundreds of companies.

Q11) If you were training a new generation of analysts or financial journalists, what would be the one habit of thinking you’d want them to internalize from this book?

Alex: To question everything and to challenge the beliefs you hold dear. See a complex issue - even one that you view as open-and-shut - as one that has two sides.

Q12) If readers walk away from May Contain Lies more skeptical, but also more thoughtful, what does healthy skepticism look like to you?

Alex: It involves discernment, but not cynicism or being a conspiracy theorist. First, we shouldn’t be skeptical of everything, because doing so wastes time and energy. We should only be skeptical about what’s important. We could get lost in a rabbit hole looking at restaurant reviews not only on Opentable, but also Google and other platforms, and not only look at the star ratings but read the comments and study which are the most recent. But, eating at a slightly better restaurant would likely have a small effect on your life. Second, research is only valuable when the main objectives are measurable, and thus ripe for analysis. Few parents choose between football and rugby for their kids based on which leads to the best health outcomes or instills the best character - instead, they may base it on which sport their kids love the most, what their friends are doing, and which has the most convenient schedule. But third, where something is important, such as the effect of alcohol on your health, breastfeeding on child development, or sustainability on investment returns, to study it very carefully and take the quality of data very seriously.

Q13) Finally, has writing this book changed how you read the news, research papers, or even academic work? Are there things you now consciously avoid believing too quickly?

Alex: I try to challenge everything I write. For May Contain Lies, several literary agents offered me representation, and the one I went with was the one who was most critical about my proposal, as I thought he would have greatest potential to improve it. I’m now writing another book, The Madness of Markets, on the psychology of finance, and sending it round to people I trust to ask them to criticise it. Now with ChatGPT, I can use AI to poke holes in what I write. This extends beyond books or research papers; I often use it to scrutinize a draft email on a sensitive issue to ensure that it’s not misinterpreted, or an email that I’ve received to ensure I’m not reacting to it in an emotional way.

Thank you all for reading and a big thanks to Alex Edmans for collaborating in today’s post!

It’s a pleasure!

Readers who wish to follow Alex Edmans’s work more closely can visit his website for books and essays, consult his Google Scholar profile for academic research, or follow his writing and commentary on LinkedIn, Instagram, and X. An overview of his career is also available on Wikipedia.

Website: https://alexedmans.com/

LinkedIn: https://www.linkedin.com/in/aedmans/

Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/aedmans/

Wikipedia: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Alex_Edmans

Google Scholar: https://scholar.google.com/citations?user=_UHUfFsAAAAJ&hl=en